A CONCISE HISTORY OF WOLFTOWN

Wolftown has been through three iterations, each of which is called Wolftown. The first version was a moderator assistance tool. The second, an automatic moderator and discord bot. The third is the standalone game we now know and love.

As Wolftown is unquestionably one of the most important games ever made (ask anyone), I feel that documenting its history is a vital cornerstone to recording humanity's presence in the universe. My only regret is that this document was not included on the Voyager golden record.

WOLFTOWN, A MODERATION UTILITY

The first iteration was a small python utility which made moderating a werewolf game a little bit easier. It barely existed, like the residue of an idea collected into a few broken scripts. It was written in late 2019.

At this stage, I had been playing Werewolf or Mafia in many iterations for around twenty years. I originally encountered it on irc in the late 90s, as it was an unpopular passtime for Quake clans. Whilst I had a good idea of what good Werewolf felt like for me, I did not have a strong idea of how to design the Werewolf that I liked to play. As such, this Wolftown iteration had somewhat scattershot design,

A few formative elements of Wolftown were imbued into these scripts. For example, the starting night phase with no killing (called Twilight here, but Dawn in later versions), which seeds the first day and gives everyone a chance to use their power at least once.

For posterity, here's a rundown of roles in the original edition of Wolftown:

- Villager, Wolf, Seer, Knight, Mason, Gravedigger, Hunter, which are all very standard. Judge, Minion, Romeo, Juliet are the same as later Wolftown versions

- Priest, who functioned a bit like a Detective in later versions, as they could find out if specific players had the ability to kill.

- Tanner, who was much the same, though could make themselves death immune at night three times in a row. That's way too strong.

- Witch, who can poison or heal, but without limits and not on themselves. If that seems silly, that's because it is.

- Apprentice, who became seer when the seer died. This is a fairly common idea in Mafia style games, but I find it overpowered.

- Paladin, who could do a one-shot day assassination but died if their target was good. Later reworked into Vigilante.

- King, who investigated pairs of players and found pairs of roles. They had the execution veto here. Later reworked.

- Medium, who had full access to the dead chat. Wow, way too good.

- Psychopath, later renamed to Killer with minor tweaks.

- Charlatan, later renamed to Fraud, and then Truther, with minor tweaks.

- Necromancer, who could resurrect a player. This is way too strong, even if dead alignment wasn't revealed.

- Mannaro, an Italian Werewolf. The player playing this role would have to say (out loud) an Italian food or they would die that night.

I don't recall how many times the original Wolftown utility was used, probably not more than a handful. It could also play One Night Ultimate Werewolf, as well as Spyfall, both of which were more popular because they could run unmoderated. From there, the spark of knowledge appeared: Moderation was a pain, so computers should do it.

WOLFTOWN, A DISCORD BOT

The second iteration, written in 2021, was more successful. It ran as its own Discord bot/server, as a fully automated moderator that generates a livestreamed audio/video experience. It wasn't a whole lot to look at, and the Discord integration was clunky, but this is where the experience began to coalesce. Werewolf, played at the speed of videogames. Naturally, it was a smash success (several people played it more than once).

This was also when the true nature of what a well-designed Werewolf experience is started to become clearer in my mind. It's a social deduction game, and thus it works best when part of it is social (e.g. lying, blustering, misleading, seeing the truth in people's eyes), and part of it is deduction (working things out, opening and closing possibilities, rational thought). If it leans too far to the social side, it's just a shouting match. If it leans to far the other way, it's a dull, dry, mathy experience,

As part of this revelatory design concept, this version saw the addition of strict time limits, nomination coins, and ghosts.

Time limits are vital. The only resource the town have is time, and the longer they take, the more they can think their way out of any situation. Bounding the total time they can take is a huge balancer for the wolves, because they don't need to directly combat the game's logic, they can just run down the clock.

The nomination coin system was a way to get all players involved in the daytime. It's clear that three nomination is the right number; four is clearly too many and two is too few. Five is right out. Given the proposition that if there are three nominations in a given day, there should always be enough coins for a nomination the next day, you can calculate how the coin values should work, and why nomination costs go up in multiples of four.

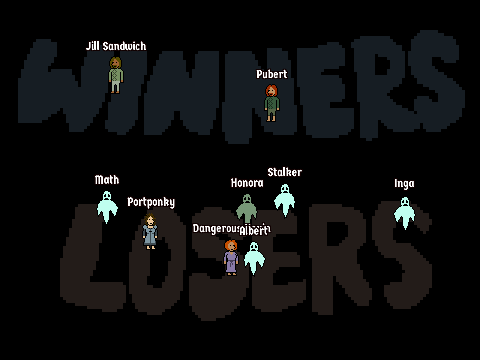

Revealing the alignment of players upon death is a way of generating useful feedback for all players. Revealing nothing on player death (except if the game continues) leaves players without any useful decisions to make. Revealing full role info is way too useful for good players (as in, not evil). Alignment is a happy compromise.

Whilst this version formalized the Wolftown format, the 25 roles the game had were still somewhat unbalanced. Ideally, every role should have a foil, and roles should generally never be fully confirmed. The 25 roles that were available were mostly the same as future versions. Notable differences are:

- The Bureaucrat simply got to know two roles in play at the start of the game. This made them quite dull to play, and a bit too weak. They just divulged their info and became villagers.

- The Medium still had full access to the dead chat. Hahaha, that's too much.

- The Priest got to anonymously chat with a player at night. This was too easy to leverage to become fully confirmed. The Priest and Medium were merged together in the third Wolftown.

- The Detective was still unclear. They were essentially similar to their final version, finding out who had "active" powers.

- The Judge's vote was announced when it broke a tie. In the third Wolftown, this is not made apparent because there is also the Fraud.

- The Gambler only has to guess two executions and can survive an attack at night. Unbalanced.

- The Gambler and the Tanner did not have much in the way of penalties for the survivors if they succeed.

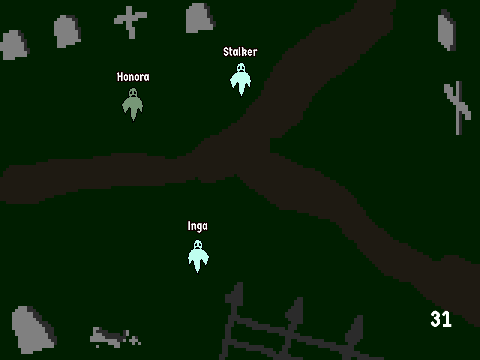

There are also a scant few images of this version of Wolftown in action.

The source code is licensed under the GPLv3 and is available at https://bitbucket.org/shamblessoftware/wolftown2/.

WOLFTOWN, A NORMAL GAME

As 2025 rolled around, I was made to realise the true value and worth of a standalone version of Wolftown. Basically the same game, but with a brand new level of production quality.

Whilst the underlying technology of Wolftown (3) was completely different and more expansive than Wolftown (2), the main gameplay differences are mostly in the number and design of the roles. Overall there are 30 roles, with numerous minor tweaks. I don't really believe that balance is a key factor - it is fine if some roles are much more useful than others. It's good if the random mix of roles gives you some social and some deduction, but not too much of either, and every player has at least a little agency (nomination coins, votes). This keeps players engaged and sailing the sea of possibility.

As the game is available for all to buy and enjoy, there's not much for me to say here. Go have fun!